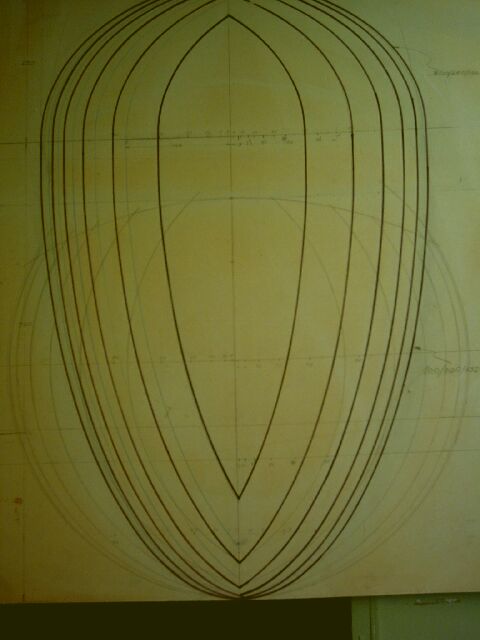

Photo 1 - the conventional catamaran hull and my MK 2 hull (faint outline) cross-sections.

In the last installment I published the design of a conventional catamaran hull for comparison with my MK 2 hull - photo 1 shows their hull cross-sections.

Photo 1 - the conventional catamaran hull and my MK 2 hull (faint outline) cross-sections.

In the following I present my reasons for the MK.2 hull design with particular reference to my requirement for launching and beaching my catamaran through surf.

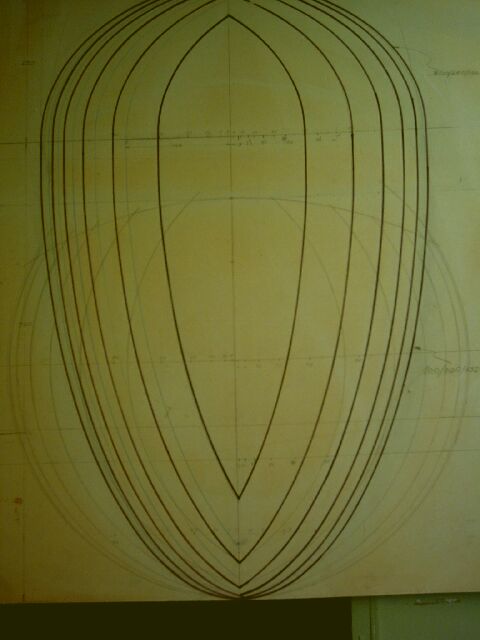

The shape of MK 2 hull is based largely on my white-water canoeing experience with the Canberra Canoe Club and the canoe shown in photo 2.

Photo 2 - Shoalhaven River, Bombay to Warri bridge 12 kms. My first Platypus, a slalom C2 developed by Rivers Canoe Club. Paul McKenzie up front.

The Platypus is a slalom canoe and has no transverse stability - so it requires very little effort to capsize, but can be rolled upright - by expert canoeists. It offers very little resistance to the water impacts produced by the white-water turbulance as all of its surface is curved allowing the water to flow freely over it. In sailing boat terms, it has no noticeable lateral resistance and very low hull-drag.

The white-waters as shown in photo 2, are much more turbulent and dangerous than sea-beach surf. The Platypus can be controlled in these waters with relative ease by paddle strokes- although Paul and I capsized many times. Because of its low drag the Platypus could be paddled uptream, so we learnt how use the vortexes in rapids to help us paddle upstream and surf stopper-waves. I think all this canoeing gave me an appreciation of the forces to be expected in a rough sea.

The Club also ran training session at surf beaches so I learnt about surfing in a kayak. This involves coming in through the surf broadside-on to a wave whilst staying upright by maintaining a support paddle-stroke on the wave-side of the canoe. Come through the surf at a right-angle to a wave and you risk pitchpoling - which is a rather frightening. I experienced broaching in various canoes and that helpless feeling that goes with it.

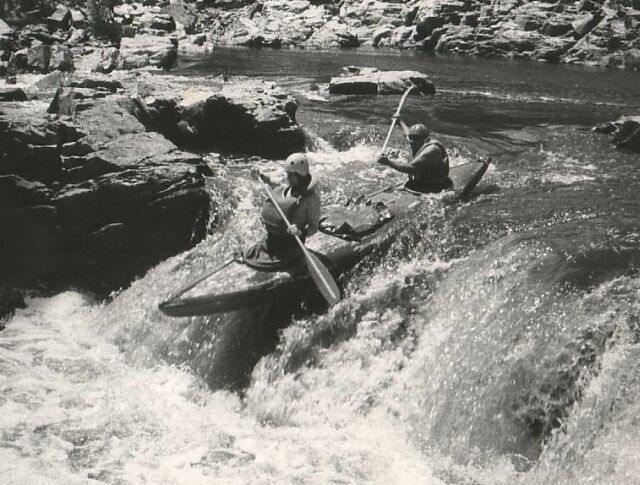

The more I learnt about this white-water the more it began to frightened me - particularly the force of the fast-flowing water, stopper waves and the lethal submerged tree-roots below beautiful willows along the river banks. So after 4 years of canoeing, I added an outrigger to the Platypus - as shown in photo 3, and used this proa for touring the sea coast and as a spearfishing platform. Its tubular outrigger does not produce any noticeable drag and resistance to movement of the sea - the reason why I favour tubular outriggers for my proas and trimarans.

Photo 3 - Platypus proa - a very useful canoe. It was stolen from this riverbank in February this year.

Photo 4 - The Platypus proa - Andrew, Barry and Adam. A great craft for surfing waves.

But back to the present subject and a significant happening - the day Adam and I caught a wave in the Platypus proa. We surfed down its face and slewed beam-on into a classic broach with the outrigger on the wave side. We finished up in the water and were surprised to see the proa was upright, even though it must have almost rolled right over to dump us in the sea. Ultimately I came up with the following answer to this puzzle. Referring to photo 5 covering a canoe training-session about how to enter a fast-flowing stream. This involves pointing the canoe 45 degrees upstream, paddling out from the riverbank followed by turning downstream with the drawstroke by the bow-hand, whilst leaning-out downstream. At the time I did not understand why we did not capsize. Now I know, the flow of water under the canoe produces by skin friction, a righting torque opposing capsizing. Which in the case of the Platypus proa happening described above, explains why the proa righted itself.

Photo 5 - training session about entering a rapid from the river bank. Bow hand Wendy Zarb.

So from all of these experiences I adopted the following design rules and tactics for negotiating the surf with my Windrigger craft. Hulls with circular cross-section, symmetrical fore-and-aft and minimum freeboard - sufficient to satisfy adequate reserve buoyancy. Fot a catamaran, open space between the hull deck and underside of the bridgedeck to allow the sea to flow through the space unimpeded.

Beaching through surf tactic - no fins, rudders and keels in the water when passing through surf to a beach. Just leave it to the sea to push the boat ashore.

When passing from a beach out through surf under sail - some centreboard and rudder in the water are essential to make way through the waves. These requirements are achieveable with the centreboard and rudder systems shown in photo 1 of the Dec 2004 installment and photo 6 below.

Photo 6 - Windriggercat 6800 as trialled Feb/march 2005, showing the new aft-cockpit.

Photo 7 - Windriggercat 6800 showing detail of the liftup/kickup rudder.

So all of the foregoing are my reasons for the way for the radical features and appearance of Windriggercat 6800. It now remains for me to trial it the surf.

Back to my canoeing experiences - in our club we built our canoes by fibreglass from moulds made by club-members and or borrowed from other clubs. I built 3 canadians, 2 Platypus and a slalom kayak. The rivers we canoed seemed to me are mostly 50% rock, so our canoes had a life of not much more than 2 years. I learnt about hull construction from canoeing which 10 years later, used this experience in design and contruction of my MK 2 hulls. This is the subject of the next installment.